Halyna Kruk is a Ukrainian poet, children’s writer, translator, literary critic and professor of medieval studies at the University of Lviv. She has also been a vice-president of PEN Ukraine.

Olesya Zdorovetska is a performer, composer, curator and educator. She is the founder of the Ukrainian-Irish Cultural Platform.

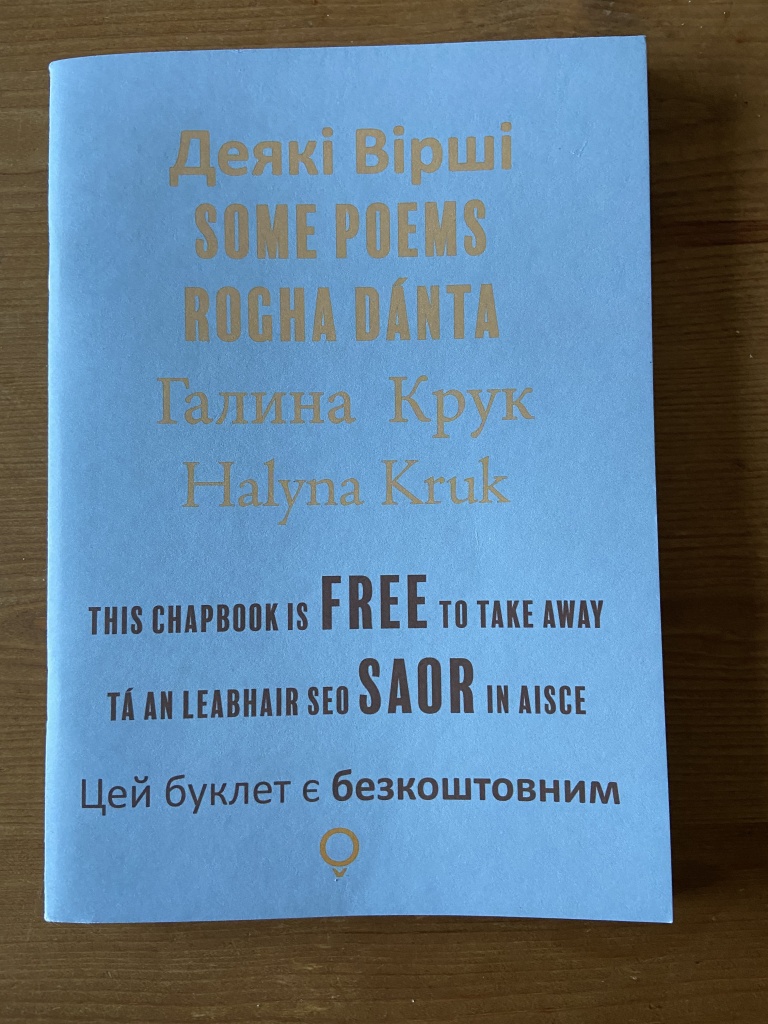

We are in Rathmines Library to listen to a conversation between these two women and to hear Kruk reading from her work. Poetry Ireland, Literature Ireland and Munster Literature Centre have co-sponsored a chapbook of her poems Some Poems. The poems are printed in three languages: Ukrainian, Irish and English, and they are available free to everyone present. The audience is roughly 50% Irish and 50% Ukrainian. I’ve tried to paraphrase what we heard in the conversation as accurately as possible.

As we come in to the room, news is breaking that more than a hundred rockets have been fired into Ukraine by the Russian army, and that two people have been killed in Poland, near the border. The room crackles with this news, but we settle down to listen. Kruk speaks in Ukrainian and Zdorovetska translates what she says.

Halyna Kruk (HK): Writing, literature and journalism, helps to describe and grasp what is happening in this war. That’s why I do it. But a problem emerges when you express your own experience: it’s hard to explain or translate what you’ve lived through. Living through it is already enough.

The experience of Ukrainians is divided. There is life on the frontline, people dying next to you. That’s one experience. If you’re in a bomb ‘shelter’ (not proper shelters at all) or in a metro station with your children for a month, that’s another experience. People who managed to grab their kids and leave – that’s another experience of living through war. They don’t suffer less. If part of your family stayed, they are in danger, you worry about them. There are different experiences – and collective experience.

(And, for example she is worried about her father who is in hospital in Lviv. He needs oxygen, and there is no electricity.)

Olesya Zdorovetska (OZ): What is your experience of travel, of speaking to people (outside Ukraine) – how is Ukraine perceived & what questions are people asking?

HK: For example, recently I was asked about ‘how suddenly Ukrainian literature has appeared…’ I had to explain that Ukrainian literature has always existed but the Russian narrative is so overwhelming that Ukrainian voices are not heard. One of the biggest issues is (the lack of) translation. Every European university has Slavic Studies but only three have Ukrainian studies

(From the audience: It’s always Russian studies.)

In every city Kruk is asked strange questions, but now there is a chance to talk about Ukrainian arts and culture.

Usually, interest is sparked in Ukrainian literature after a reading. She hopes they can use this opportunity to promote Ukrainian culture more broadly.

‘It’s hard to talk about culture when there are sudden power cuts, no internet, etc – but people keep working in such conditions in Ukraine.’

‘As an artist I’m upset because this theme of war will last for twenty years and we will have to make sense of it.’

‘I’ll have to rethink how to teach literary history.’

She reads poems which are not in the chapbook, poems that have been written since 24th February. One is written with Europe in the background. ‘Take us in,’ is a refrain. Another, she explains, is called “My Hate Language” but her language, the language of poetry, is actually the language of love. The poem is against hate speech/incitement to hatred.

OZ: (On language): People need to stop saying that current global problems (the cost of living, oil prices) are ‘because of the war in Ukraine.’ Instead, we should say ‘this is because of Russia’.

She adds that, ‘In Ukraine, now, the whole country thinks as one. … If you are Ukrainian, no matter where you are in the world… It’s amazing. There is so much compassion, kindness, common sense out there …’

HK had a very personal experience in Lviv (2014). ‘Millions of people were escaping to safety, mostly women and children. You could see people on trains in their slippers, with kids and animals in their arms. When they arrived at the station, they couldn’t understand why people were giving them tea and sandwiches. They had so much pain and frustration, they couldn’t understand this. That was one of my hardest volunteer experiences, being there, making sandwiches and talking to them. It was hard. There was so much anger. So much fear. My fists clenched. But you have to unclench your fists and make the sandwiches and pour the tea. This experience will stay with me.’

“You have to unclench your fists and make the sandwiches and pour the tea.”

At the beginning of the war she started a diary – ‘Many writers have done this – capturing what’s going on, trying to make sense of it. Because every day brings new challenges and you forget what happened before. Wartime has this effect. At some point you have to just exhale. So many people around you are experiencing loss. On social media, we are afraid of seeing photographs of people we know – are they dead? What has happened?’

On the question of humanitarian aid going to soldiers in the Ukrainian army: ‘These soldiers are atypical, not professional. Support for them in the form of clothes, blankets, what will keep them warm and help them to survive, that is humanitarian.’

OZ: How do you answer the question of reconciling pacifism with fighting?

HK: We are asked, are you pro-war? I have to explain that if people hadn’t taken up arms I probably wouldn’t be here, wouldn’t be able to talk to you – I’d probably be dead. You have to calibrate your politics – where are you pacifist and where do you take up arms and defend? War is not black and white. Everything is different now

Interaction with the audience:

- Question: What was your preoccupation in poetry before February?

HK: I had different interests. I write in a Baroque style, I use wordplay, it’s tricky to translate because it plays on Ukrainian sounds and language. I get inspiration from everyday language, what’s on the tip of the tongue and what’s on people’s minds in the moment … a poem can be about everything and everything can have poetry in it. There is a lyricism in Ukrainian that is hard to translate. At the beginning of the war it was difficult because I lost my language. I lost my words. I couldn’t write.

OZ: In Ireland there is democracy. Don’t take it for granted. It’s brilliant to be here, where you won your independence, 100 years later. You have such strong institutions that support the arts, like the Arts Council and the Libraries. The libraries are brilliant, more than libraries. They offer facilities, opportunities … our Ukrainian institutions are in danger now.

“War is not just about territory and killing.”

War is not just about territory and killing. There is the destruction of art and culture too. They steal – for example in Kherson … art has been stolen and destroyed. Please support us in any way you can. There are great museums in Ukraine – some you can follow online, Ukrainian institutes with resources in English. For example:

“Postcards from Ukraine” (shows images of buildings ‘Before’ and ‘After’).

HK: One of the worst aspects is the loss of institutions and unique art and artefacts, the kind of resources that are hard to restore, for example the Museum of Embroidery in Kyiv region. These are not military targets but cultural. This war it is starting to look like a war of barbarity.

OZ: We have so much to speak about here, like the experience of being a post-colonial place – we have much in common with Ireland – language – famine – the Ukrainian Ambassador is putting together an exhibition about our famine. And language – I miss hearing Irish (in Dublin) It’s a gorgeous language, I love hearing it in the west.

(From the floor): There are so many parallels between Ukraine and Ireland – the Ukrainian language is more alive. Without language you have no soul; language and music are our legacy.

(Reply from the floor): 20 yrs ago we had the same problem in Ukraine but we’ve made good progress since then.

At this point Gréagóir Ó Dúill stood up and said that language is the core of every culture. He points out that we haven’t heard any Irish here tonight but there are Irish translations in the chapbook. He would like to read one of the poems and he does read “Mama/ the mother/ an mháthair”, to huge applause.

Shortly afterwards, the bell rings to let us know the library is closing and we say our sincere thanks, appreciation and goodbyes and go out into a chill night, checking our phones and news apps to find out more about what happened across Ukraine and in Poland this evening and how it might affect the course of the war.

Thanks for this, Lia. These events are important.